Today on The Disability Tribune, we welcome award-winning poet, activist, and arts educator Meg Day, who has a new collection of poetry that just hit the shelves called Last Psalm at Sea Level (Barrow Street Press, 2014). She is also the Poetry Editor for Quarterly West and is currently a PhD fellow in Poetry & Disability Poetics at the University of Utah.

Belo Cipriani: What is the title of your book?

Meg Day: The title of my first full-length collection of poems is Last Psalm at Sea Level and it will be published by Barrow Street Press on October 1, 2014.

BC: What is your book about?

MD: What a deceptively simple question! I began thinking through this book when I lived in California and completed it after a few years in Utah. Before moving to Utah, I had never lived away from a coast (and never far from an ocean); when I found myself landlocked for the first time, everything changed—not just my work, but my health, my sense of self, my cravings for happiness, my personal and romantic relationships, my professional aspirations, and my desire for family. Last Psalm at Sea Level is, for me, a farewell to the life I thought I knew, but also to California—it’s hard for me, as someone so invested in and affected by geography, to separate them out. I don’t mean to say that I won’t ever live in that great state again, but I think there’s an insular quality to California that comes with a particular fetishization of life there and bestows upon its residents, especially those raised there (like I was), a sense that nowhere else could be as great a place. In leaving California, I had a lot of mourning to do; and then, later, when I realized how foolishly I had discounted so many places in the country (and thus, so many kinds of lives I might’ve liked to live), I mourned what kind of possibilities I’d missed because of my coastal blinders. It’s a book about the in-between of all of that, about in-betweenity in general, I think—and the interrogation of geography as dictator, and of god, whoever or whatever that is, as something else entirely.

BC: How long did it take to write?

MD: There are a few poems in this collection that I began as early as 2006, and a handful in 2010 at Lambda, but the great majority of the book was written from winter 2011/2012 through winter 2012/2013. I’ve never produced that much work in such a short amount of time, but believe me when I say it was a long, long winter, even through the hottest parts of July.

BC: Where did you write the book? Did you have it workshopped?

MD: I wrote the book mostly in-residence in Salt Lake City, but some poems are, to me, very obviously written while traveling in coastal San Diego, in the hills of Los Angeles, or in a restored boomtown in Centennial Valley, Montana. A good number of them are written in airplanes, flying above much of the western United States, or as a passenger in cars, driving across it. I was lucky to have the editorial help of colleagues and faculty in my PhD here at University of Utah, but am also indebted to early comments from workshop participants and facilitators at Lambda, Squaw Valley, and Hedgebrook.

BC: Was there a part of the book that was particularly tough to write?

MD: Am I allowed to say all of it? There are many poems in this collection that deal with the difficulty of being alive, whether that’s through standing witness to illness or heartbreak or some other trial altogether. As the book started to take shape, so many people in my life were enduring some crisis or another—family trauma, transitions, sobriety, cancer, suicides, injuries or arrests during the height of the Occupy movement, displacement, divorce, hate crimes—and poetry became this mental space where everything was possible and everything finally stood still. I could breathe in poems, I could catch my breath, I could take a break from the incredible labor of living. It was difficult, though, to figure out how to best represent some of these stories without appropriating their experiences. I don’t mean to imply that every poem is non-fiction—far from it—but instead to sort of preserve my position as witness. Korean poet Myung Mi Kim talks about how it is that we can tell stories without being at the center of them: we stand next to them, we offer them support, we hold them up.

BC: What is your creative process like?

MD: I really like to think about things for a long time before trying to put them on the page. Nobody ever really likes that answer, mostly because some folks seem to be really invested in believing that there’s only one recipe for being a working writer and it involves sitting for a certain amount of time every day, churning out work. It’s just not how it happens for me. I definitely “work” every day, but because I’m invested in particular relationships and in spending a lot of my time teaching, sitting down to write for hours every day not only seems undoable, but totally unenjoyable. I remember trying it during undergrad (to no avail) and finding it felt a lot like trying to sleep when you’re not tired: ultimately, it dissuades you from lying down at all. So mostly I think a lot. And read a lot. Sometimes I write things down in a notebook or accidentally on the back of a student’s paper. Sometimes I listen to a song on repeat for too many days and the repetition makes something new happen in my brain. It’s exciting that it’s different every time. I like that there’s not one answer.

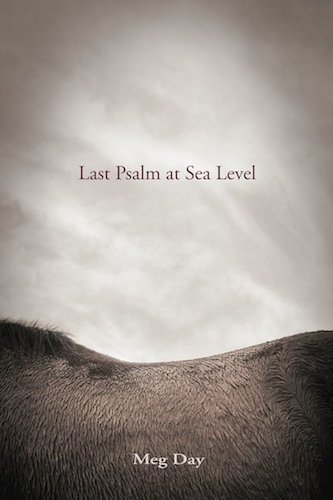

BC: Did you get to pick the cover and title?

MD: I’m really fortunate that Barrow Street offered me a lot of freedom in finding an image for the cover of this collection and even more grateful that Afaa Michael Weaver’s editorial notes didn’t require me to change the title. The title decision was a long time in coming and was the focus of a lot of my worry early on in submitting this manuscript to contests (it was a finalist at six other presses under a total of four different names!). Typically, contemporary publishers shy away from any kind of religious reference—one press wrote back and merely said that any book with the word “god” in it was going to be a hard sell. It’s not that I don’t believe them, it’s that I watched them become too distracted by the connotation to understand what was possible in language play. I don’t frequently find myself compelled by poems that address “God” in the traditional, conventional sense, in the same way I’m less interested in poems that address the “muse” as we saw it in the epics. I like different and deeper investigations. What about the divine self that exists but is untouchable, ineffable? What about a lord that is female and eternal and transgender? I’m interested in remaking god again and again through language. I’m interested in reclaiming the divine for poets who look upward when they write.

The image on the cover is by Sarah Treanor, a fine art photographer living south of Austin, Texas. I was struck by the incredible vibrancy of Treanor’s work and especially interested in the way that she captured on film the private pastoral interiority that carpets a lot of my poetic intention. Before I knew anything about her, I was certain that she was a photographer who had dealt with loss or grief, simply because her images are nuanced in a way that is altogether animated and also full of longing—they visually embody the elegy at its best, without losing that pastoral heritage. I’m really lucky that Treanor agreed to work with me and luckier still for the artistic collaborations that I think are possible between us moving forward.

BC: What are your thoughts on ebooks? Will there be an ebook version of your book

available for purchase?

MD: Ebooks are swell! They’re sometimes a little more affordable, they provide flexibility around sharing and traveling, and, perhaps most importantly, they improve access for folks who require screens or magnified text or voice-software in order to read. I don’t feel afraid of ebooks taking over print books, nor do I really think poetry suffers from the so-called limitations of screen or tablet sizes. Sure, I worry about my lineation being conveyed in the way that I intended it, but I worry about that in print, too. Some pages just aren’t wide enough or long enough for my lines; it comes with the territory, I guess. More frequently, however, I find that ebooks or web-based literary journals are better equipped to accommodate. I feel excited about what ebooks and electronic literature make possible. If it improves access, I’m for it. As for this particular collection, I don’t know that there’s an ebook currently planned—but here’s hoping!

BC: To whom did you dedicate your book and why?

MD: In early conversations with Barrow Street, I made the unpopular decision not to dedicate my book to anyone. It just seemed like such a loaded thing for me, a political thing, like who you invite to your birthday party and who you don’t: leaving folks out by having to choose a few for the dedication wasn’t appealing to me. Because this is the first book that I’ve published, but not the first chapbook or the first manuscript I’ve completed, even, it’s difficult to figure out how to best express gratitude to the folks who were crucial in this particular project’s fulfillment, without also including every single poet, teacher, partner, chosen kin, or classmate that helped me arrive here. I think folks expect the latter from first books, but this isn’t really my first book—it’s just the book that got picked up first. Should my very first manuscript ever become a published collection, the acknowledgments might, by then, appear to be some archive or cemetery of relationships gone by. Even then, I think I’d probably shy away from dedication. My book is for you, is for the reader, whoever you are.

BC: When and where will your book be available?

MD: Last Psalm at Sea Level is currently available through Amazon, Small Press Distribution, and through Barrow Street Press’ website. The book’s official date of publication was October 1, 2014, but I think everything’s a little backordered already. I’m really excited to be touring with the book this next academic year and would love to roll through as many schools, libraries, book groups, community centers, youth groups, or book festivals as is financially feasible. The best part of writing, hands down, is the community that builds up around it.

To learn more about Meg Day, visit her website at www.megday.com, find her on Facebook and follow her on Twitter @themegdaystory. You can also visit her author pages on Amazon and GoodReads.

Who is Belo Cipriani?

Belo Cipriani is the Writer-in-Residence at Holy Names University, a spokesperson for Guide Dogs for the Blind, the “Get to Work” columnist for SFGate.com, and the author of Blind: A Memoir and Midday Dreams. You are invited to connect with him on Facebook, Twitter, Google+ and YouTube.