By Belo Cipriani

Some people prefer to communicate with words, while others find images more telling. For gay San Francisco resident Kurt Schwartzmann, drawing has always been a way to share his thoughts with the world.

“I’ve always loved to draw,” said Schwartzmann. “My parents — retired educators — encouraged my artistic abilities.”

Schwartzmann, 54, used his creative talents to launch a 20-year career as a professional pastry chef and baker. While things were good for some time, it all changed in 2006 when CMV retinitis, a complication of AIDS, attacked his left eye. The virus severed the optic nerve, and slowly and painlessly, he began to lose his vision.

“One day the doorbell rang. I went to answer and realized that I could not see anything through the peephole with my left eye,” he said.

Life became even more complicated when, in 2008, he lost his housing and found himself living on the streets.

“A Muni operator showed me a great kindness,” Schwartzmann said. “She allowed me to board her bus and sleep when I had nowhere else to turn, even though I had no money to pay the fare.”

The display of compassion the Muni driver showed touched Schwartzmann and the memory stayed with him.

A few years later, Schwartzmann was back on his feet. With his troubles behind him, he finally had the opportunity to reconnect with his art. Though, it was his mate, Bruce Schwartzmann, who gave him the big nudge.

“My partner suggested that I take a printmaking class,” he said. “When I inquired ‘Why?’ he replied, ‘So you can make our wedding invitations.'”

“So,” Schwartzmann continued, “I added printmaking to my artistic repertoire. We got married in 2013.”

As Schwartzmann reconnected with his craft, he also realized he needed to talk to someone about his visual impairment and turned to the Lighthouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired in San Francisco.

“I was looking for a therapist that I could relate to, one that could help me with situations and language associated with loss of vision,” he said.

Although Schwartzmann does not use a white cane, or any other mobility aid for the blind, he found it necessary to cover his blind eye.

“I choose to wear a black eye patch,” he explained, “to communicate to the world that I can’t see on my left side.”

Schwartzmann clarified that by covering his eye, if he happened to bump someone with the left side of his body, the individual would automatically know the reason for the abrupt collision. However, some reactions to the patch have given him much to talk about.

“Sometimes,” he said, “insensitive people call me a pirate. This used to bother me, but now I just answer: ‘I am not a pirate, I am an artist.’

“As for my patch,” he continued, “a friend of mine and I designed it to fit my face. We created it out of plastic mesh and fabric. The ones they sell at drug stores are too big and uncomfortable.”

But while his lack of sight with one eye has presented him with some unpleasant social interactions, when it comes to his drawing, Schwartzmann states that it has helped with his technique.

“Having 2D vision,” he said, “flattens my perspective of the world and makes it easier to transfer it to a flat piece of paper.”

“To me,” he continued, “drawing is like dismantling a composition into its components and reproducing them on my sketchpad to recreate the whole.”

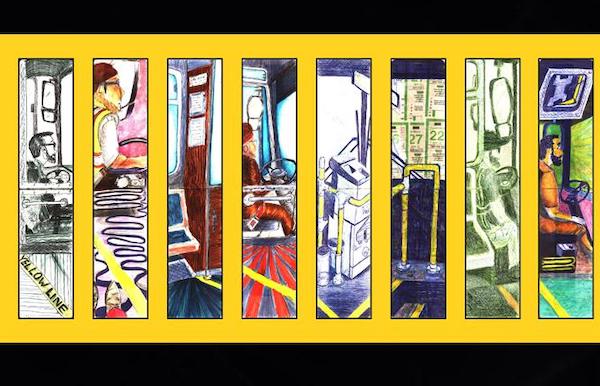

On January 10, the Lighthouse opened an exhibit of Schwartzmann’s collection of drawings: “Yellow Line: A Tribute to SF Muni Operators.” The well-attended event showcased 64 drawings that pay homage to the Muni drivers that he came in contact with while drawing the series over a three-month period.

The “Yellow Line” collection is simple, yet also complex. It possesses impressionist elements, but with a playful and primitive twist. Schwartzmann’s work is available for purchase on his online store at www.yellowlineart.ecwid.com. To reach him, you can visit his artist website at www.YellowLineArt.com. The “Yellow Line” exhibit will be at the Lighthouse, 1155 Market Street, 10th floor, until May, according to his website.